Even on a stage filled with exceptional women, Elizabeth Holmes knew how to stand out in a crowd. It was a chilly autumn evening in November 2015 in New York, and a who’s who of female power players had filled the glittering Carnegie Hall for the Glamour Women of the Year Awards. In turn, Amy Schumer, Caitlyn Jenner and Reese Witherspoon took to the stage to accept gongs and to offer impassioned and stirring speeches.

The Mayor of New York had decided to light the Empire State Building pink in honour of the occasion. While her compatriots dazzled in red carpet gowns, Holmes wore a simple black business suit, the outfit she wore every day to work at Theranos, the revolutionary medical testing company she had founded.

Her only nod to the dress code of the evening was to swap her usual black turtleneck for a hint of décolletage. But while the then 31-year-old might have lagged behind the rest of the Women of the Year pack in terms of style or household-name fame, she was clearly the night’s inspirational frontrunner.

Taking to the stage to collect the award for entrepreneurship, she implored the crowd in her famously deep voice: “It’s our actions that will determine what our little girls will look at when they decide what they want to be when they grow up.” Coming from Holmes, this message seemed more than a simple feel good, motivational cliché.

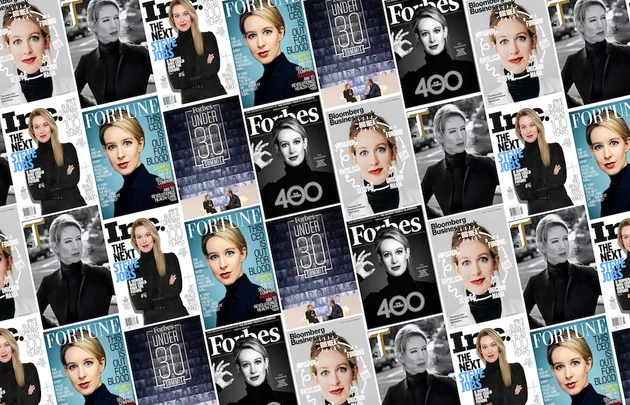

In only 12 years she had metamorphosed from a university dropout to the youngest self-made female billionaire in the world. Barely into her 30s, her company promised to revolutionise healthcare on a global scale and save countless lives. Fortune magazine had recently valued Holmes’s net worth at $US4.5 billion. Time magazine had named her one of the most influential people in the world in 2015. Bill Clinton chose to share the stage with her for the closing session of the Clinton Global Initiative annual meeting. It was even rumoured that Jennifer Lawrence was slated to play Holmes in a biopic based on her life.

Everyone everywhere, it seemed, was falling head-over-heels for Elizabeth Holmes. On that autumn night, she was at the apex of a charmed year, accepting an award for both changing the world and inspiring a new generation of young women to do the same. It’s impossible to watch videos of Holmes accepting her award now, one year later, and not wonder: did she know?

Did she know that her Cinderella story was closing in on its stroke of midnight? Did she know that her house-of-cards company was about to collapse, that within months her net worth would be recalculated to zero and that the FBI would be investigating her and Theranos for fraud?

Silicon Valley is famous for being a place where entrepreneurs’ dreams come true. Located just south of San Francisco, the unassuming area has evolved into a hothouse environment where high-tech start-up companies come to make their fortunes. It’s also where venture capitalists throw around huge amounts of money to get in on the ground floor of The Next Big Thing.

Facebook, Google and Apple are all scions of the region’s hectic, success-driven, male-dominated culture. It’s also home to Stanford University, the college Holmes attended before quitting to pursue her entrepreneurial dream in 2003. The Holmes fable goes that, spurred on by a lifelong fear of needles, she came up with the idea to create a test that could detect myriad diseases with the blood from a simple finger prick. Within months of quitting Stanford she had persuaded a slew of powerful people in the Valley that she was on to The Next Big Thing, raising $US6 million to launch Theranos and hiring the dean of Stanford’s engineering school to join the fledgling company.

Simply put, Theranos would test your blood for hundreds of illnesses, much like your doctor. However, rather than sticking a needle into your vein and taking out an entire vial, Theranos would prick your finger and take just a drop or two of blood. What’s more, Theranos would cut the doctor out of the equation. If you wanted to know, for example, if you were HIV positive, or what your cholesterol levels were, you’d simply send your blood to Theranos and they’d report the results back to a mobile app. It would be easy, fast, less painful and much less expensive, as Theranos charged a mere fraction of what a traditional medical lab would charge. As Holmes herself was fond of saying, her product allowed you to be directly in control of your healthcare information.

“The implications are mind-blowing,” enthused Wired magazine in February 2014. Standing on stage at TEDMED that September, Holmes declared: “We see a world in which no-one ever has to say, ‘If only I’d known sooner.’ A world in which no-one ever has to say goodbye too soon.” Throughout Holmes’s 20s, the company, still without a product to sell, expanded rapidly, collecting venture capital by the tens of millions and employees by the hundreds.

Theranos spent close to a decade working in secret on making its lofty ambitions a reality. Ian Gibbons, a British biochemist, was hired in 2005 by Holmes. During his time with the company, he and Theranos scientists filed 23 patents and developed technology they dubbed Edison, a device they claimed could accurately perform tests using just a drop of blood. Outside of the lab, Holmes also assembled a stellar company board that included two former US Secretaries of State (including Henry Kissinger) and a former US Secretary of Defense.

Holmes was an unusual character, and not simply because she was a woman succeeding in Silicon Valley. It seemed at times she had designed her persona to fit a Silicon Valley venture capital pitch. In a sort of stylistic homage to her hero, Steve Jobs, the late CEO of Apple, Holmes adopted a uniform of black turtlenecks. Her Jobsian traits didn’t end there. She was also a vegan, drank green juices at specific times every day, and of course, her company was her life.

Ex-Theranos staff spoke of the company’s totalitarian measures, “secrecy” and “dysfunction”

Holmes is said to practically live at Theranos headquarters and claims to not have taken a vacation in over 10 years. She likes to tell people she has never owned a television, and that her home is a modest two-bedroom. Even Holmes’s personal relationships seem to be professional relationships dressed up as something else. The family member she remains closest to, her brother Christian, is also her employee. Board member Kissinger and his wife Nancy are reported to have attempted to set her up on dates, unsuccessfully. Her mother, Noel, told one journalist, “As a parent, I do hope that at some point she will have time for herself.”

Around 2013, word came from the Theranos corporate bunker that the product was ready. By the end of the year, the company had opened more than 40 “wellness centres” around the country, most housed in Wallgreens pharmacies. Contracts to create Theranos Wellness Centres were also signed with the Safeway supermarket chain and other retailers. Holmes was fast becoming a business superstar. Fortune magazine, followed by Forbes, put her on its cover while Vanity Fair invited her to their New Establishment Summit.

Business heavyweights including Oracle founder Larry Ellison invested money. It seemed like there was no shortage of the great and good who truly seemed to have bought into the dream of Theranos. However, away from the cameras and conference stages, there were signs of trouble. For one thing, while there were plenty of venture capital investors in Theranos, no-one who actually specialised in investing in healthcare technology had chosen to do so, and for good reason. Holmes would not allow anyone, including investors, to see the technology or the scientific results from the Edison machines.

She refused to publish any data in peer-reviewed publications, which is unheard of in the world of medical testing. Instead, she insisted that everyone – investors, regulators, healthcare providers, and the public – simply take her word that the technology worked. Another red flag for those looking at Theranos closely was Holmes herself. Although she spoke frequently of transparency in public, her insistence that no-one inside or outside the company see the whole picture was troubling.

Ex-employees marie claire spoke to described a totalitarian-like lockdown on all information. If you worked in one department, you were not allowed to know what was happening in another – even if it directly affected your job. “I’ve worked in a lot of tech companies,” said one ex-employee who asked not to be named. “I’ve never been at one where no-one seemed to have any idea how their tech worked.

Some days you’d look around at the secrecy and dysfunction and think, ‘How can this possibly not be a joke?’ But other days, you’d read or hear someone talking about how we were going to change the world, how many people’s lives we were going to save, and you’d find yourself working your ass off trying to make that dream come true.”

Holmes, meanwhile, mainly stayed bunkered in her own office when she wasn’t touring doing media gigs. “We rarely saw her,” said another former employee, “and when we did, we weren’t sure that she saw us. The exception was when there was trouble in the press, and then she’d talk to all of us and tell us we were all a team, like a family. Then the bad press would die away for a while, and she’d disappear back into her office.”

Further, those under Holmes privately questioned her honesty. “Whenever anyone asked why we didn’t just publish our data and prove the doubters wrong,” recalled an ex-employee, “she would say, ‘First they call you crazy, then they fight you, then you change the world.’ But that’s not actually an answer.”

There were also rumours that Holmes was romantically involved with Theranos COO Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, the one person officially charged with overseeing her actions.

Despite issues at the company, by the time Theranos started rolling out its Wellness Centres, it had raised nearly $US700 million in investment capital, which valued the whole operation at $US9 billion. For Holmes, life as a billionaire CEO meant having a security detail and flying by herself on a Gulfstream jet. For many employees, things finally reached a head when, in 2013, Theranos’s lead scientist, Ian Gibbons, died by suicide. Gibbons was the man tasked with making sure that Edison was successful. The day prior to his death, he complained to his wife, Rochelle, that “nothing is working” despite the fact the product was about to go live, it has been reported. “Ian felt like he would lose his job if he told the truth,” Rochelle told Vanity Fair.

“Ian was a real obstacle for Elizabeth. He started to be very vocal. They kept him around to keep him quiet.” Immediately after he took his own life, the company contacted Rochelle and demanded she surrender all computers and work data from Gibbons’ home, it has been reported. No condolences were offered.

In early 2014, an anonymous company employee alleged to authorities in New York that Theranos “might have manipulated the proficiency-testing process” of Edison. (A lawyer for Theranos refuted this.) Another ex-employee claimed that some of the potassium results Theranos reported were so elevated that the patients would “have to be dead for the results to be correct”. By the end of that year, less than 10 per cent of the tests Theranos carried out were being done on Edison, a former senior employee alleged.

In January 2015, The Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou, intrigued by Holmes’s oblique explanations of how the technology at Theranos actually worked, started looking into Holmes’s empire. In October 2015, a month before the Women of the Year Awards, Carreyrou published a story which suggested that Theranos’s much vaunted technology was faulty, that most of the testing it did was done using its competitors’ technology, and that Edison’s results were inaccurate.

In June, Forbes revised its estimation of Holmes’s fortune from $4.5 billion to zero dollars

The media and the authorities immediately took notice. Six months later, it was announced that Theranos was being investigated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission and the US Attorney’s office. The following month, Theranos told federal authorities they had voided two years’ worth of blood test results that had been conducted using the Edison.

Days later, it was revealed that the embattled company was facing two class-action lawsuits over the effectiveness of their blood testing. In June, Forbes revised its estimation of Holmes’s fortune to zero dollars. The bad news kept coming with the national Medicare & Medicaid Services declaring that Theranos’s “blatant disregard for patient safety” put consumers of its product in “immediate jeopardy”. Walgreens and other corporate partners fled from Theranos as quickly as possible.

Shortly after, the government forbade Holmes from working in medical testing in any capacity for two years. For a company with seemingly no existing working technology entirely dependent upon investment capital, all of this is as close to a death sentence as you’re likely to see in Silicon Valley.

Yet the real nightmare may be just beginning for Holmes, after one of Theranos’s major investors, hedge fund Partner Management Fund LP, announced it was suing the company. It alleges Theranos “engaged in securities fraud and other violations”, The Wall Street Journal reported. (A spokesperson for Theranos said “the suit is without merit and Theranos will fight it vigorously”.)

Now, as the dust settles, a few questions remain unanswered. One is how Theranos got anyone to invest in its product at all. “People saw what they wanted to see,” suggests Duffy DuFresne, a life science venture capital investor, who when approached found the prospect of investing in Theranos ludicrous. “We all know Silicon Valley needs more women leaders, and [Holmes’s] origin story made you want it all to be true. If you didn’t know much about medical tech, maybe that was enough.”

Theranos, as it happened, perfectly met each of the investors’ qualifications, save the one so assumed to be a non-issue that it wasn’t even mentioned by DeFresne: Does the product actually work? Theranos, it seems in hindsight, was a company designed specifically to win venture capital rather than one designed to save lives.

In the weeks and months since her fall from grace, Holmes has seemingly proceeded unbowed. In an open letter recently posted on the Theranos website, she announced the company will exit the lab-testing business, lay off 340 employees and focus on developing a miniLab platform led by a new executive team – with herself at the helm.

But the biggest unanswered question remains Holmes herself. Was she a con artist from the beginning? A foolish dreamer with noble intent, who started with one lie that snowballed, until she herself was unable to stop what she surely knew was coming? Or, despite all evidence to the contrary, was she on to something all along, that – given just a little more time and money – really will change the world?

FORBES COLLECTION/CONTOUR BY GETTY IMAGES

FORBES COLLECTION/CONTOUR BY GETTY IMAGES