“How are you out there? You feeling OK?” It’s two o’clock on a Sunday morning but 400,000 people – tired, hungry and mud-slicked from two days of camping in woefully ill-equipped conditions – roar back. With her wiry hair, wreath of beaded necklaces and tie-dyed bell-bottoms, the woman on stage could easily pass for one of them. Until she begins to sing.

Launching into a rendition of “Try”, Janis Joplin’s Texan-tinged drawl – more pronounced than usual thanks to a lengthy backstage wait and a steady supply of drugs and alcohol – transforms into a primordial wail of power and vulnerability. Shaking and dancing in a show more akin to an exorcism, her ramshackle demeanour metamorphoses the minute the band strikes up; her body a conduit for the music. Still, the voice that launched her career just two years earlier at the Monterey Pop Festival wasn’t at its finest. In fact, the Woodstock performance was subpar by Joplin’s standards and she was reportedly so disappointed that she refused to release recordings. As her friend John Clay once quipped, “That’s what really gets me … Janis Joplin was blowin’ America’s mind at half power.”

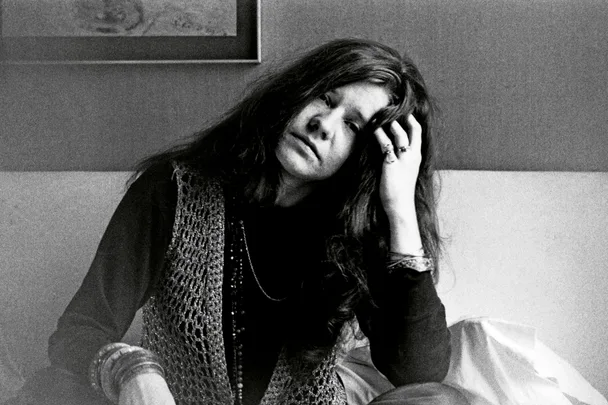

Joplin performing at Woodstock Music Festival in 1969

Though she cultivated a public image as a woman who could drink, sing, swear and have sex with the same abandon as any male musician – a stark contrast to the serene, flower-child pin-ups of the day – the industry’s quintessential wild child began life in the mild-mannered town of Port Arthur, Texas. Born in 1943 to Seth, an engineer, and Dorothy, a registrar at a business college, Joplin’s quiet disposition hid the gentle hum of ambition. Her parents fostered her independent spirit, but it wasn’t until the final years of high school that she began to reject the archaic values of her home town. She expressed support for integration at a time when Port Arthur still had an active Ku Klux Klan chapter, and was mercilessly bullied, her persecution compounded by acne and weight fluctuations. “They don’t treat beatniks too good in Texas,” Joplin once said.

Styling herself as “one of the boys” – outrageous and quick-witted – allowed Joplin to escape some of the suffocating small-town dogma, as did frequent road trips to Austin and New Orleans, where the jazz of Bourbon Street served as an early musical education. Around this time she discovered her two great loves: Odetta, the blues singer whose voice she had a gift for mimicking, and Southern Comfort, the drink that would become her totem and her curse.

After a brief stint in LA’s Venice Beach, she returned to Texas in 1961 to study art in Austin. This period of stability was short-lived, however. When the university fraternity humiliated Joplin by nominating her “Ugliest Man on Campus”, her already tenuous self-esteem was crushed. “It was the saddest thing,” recalls her friend and fellow musician Powell St. John. “To that point, I had never seen Janis cry.” By the time her mother received an anguished letter, Joplin had already packed for California.

“She definitely needed people to tell her how great she was, needed that [ego] stroking all the time,” says Jae Whitaker, her former girlfriend. When she met Joplin in San Francisco’s North Beach in 1963, the city was in the midst of upheaval. The last vestiges of the beat generation were giving way to the civil rights movement and a thriving folk scene, and Joplin started making a name for herself singing in coffee shops. Best of all, no-one made fun of her unconventional clothes or opinions. Here, an interracial lesbian couple could be left alone. She took to booze and speed with gusto and romanced a string of men and women.

“I don’t think she was with girls to shock people,” Whitaker said. “I think she was with girls because that’s what she felt in the moment.” Following the breakdown of that relationship, she became engaged to a con man who nurtured her growing speed habit, and wound up right back where she started: living with her parents in Port Arthur. Though she tried to fit in, dressing modestly and studying sociology, it wasn’t to last. After watching Joplin’s raw, gutsy, performance, a family friend reported back to her mother, “Dorothy, you don’t stand a chance.” She was right.

Returning to San Francisco in 1966 to audition for an emerging rock band called Big Brother and the Holding Company, Joplin told a friend she was “scared to death” her voice wasn’t good enough – a suspicion she constantly harboured – and that her sobriety would not withstand the city’s thriving drug culture. She got the gig.

As the vocalist for Big Brother and the Holding Company, Joplin’s address in the Haight-Ashbury district placed her at the ground zero of America’s hippie counterculture. Joplin was a regular at 710 Ashbury Street, and she traded her Texan attire for the trappings of a freewheeling gypsy. “She was just funny, unassuming, sexy, with almost a Huck Finn innocence to her. The child-woman ideal of the Haight,” Rolling Stone magazine’s David Dalton recalls. Though she tried to avoid hard drugs, former bandmate Dave Getz recalls watching Joplin swig from a magnum of wine – oblivious that the bottle had been dosed with 68 hits of LSD. But the evening’s most mind-altering event was yet to occur: seeing Otis Redding sing for the first time.

His emotional vocals and frenetic performance so enraptured Joplin that she returned to all of his shows at The Fillmore that weekend, arriving an hour early to secure the best position. Just two years later, she would share the bill with him at the Monterey Pop Festival, and, displaying the same barely contained power, land Big Brother a Columbia Records deal on the strength of a single performance. Newsweek and Time brimmed with enthusiasm. “Had I wanted to ‘hype’ her, I would not have had the chance,” wrote Myra Friedman, Joplin’s biographer and former publicist. “Janis was the only pop singer in history to become a superstar without even having what could be called a record.”

The media focus on Joplin caused tension in the band, while the influx of cash allowed her to indulge in rockstar tendencies. She famously hit Jim Morrison over the head with a bottle during a boozy meeting gone awry, and started dabbling with heroin. While recording their album, Cheap Thrills, the band stayed at New York’s infamous Chelsea Hotel, a hotbed of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. There, Joplin met an aspiring songwriter called Leonard Cohen, who immortalised their one-night stand in his song “Chelsea Hotel #2”. “She wasn’t looking for me, she was looking for Kris Kristofferson; I wasn’t looking for her, I was looking for Brigitte Bardot,” he told Rolling Stone. “But we fell into each other’s arms through some process of elimination.”

Despite Joplin’s reputation, Elliot Mazer, the editor on Cheap Thrills, remembers her near-obsessive dedication to the studio, telling Friedman, “Only Janis, myself and the engineer would stay, until [7am] … I never knew an artist that worked harder.” Cheap Thrills reached number one and stayed there for eight weeks, immortalising Joplin’s seminal versions of “Ball and Chain” and “Piece of My Heart”. A month after its release, the band split.

The following years were tumultuous for Joplin. Her new group, Kozmic Blues Band, lacked cohesion and criticism began to take its toll. The Marin County home she had purchased to escape pressures and temptations became an extension of them. In 1970, she briefly moved to Brazil in an effort to “get clean” and began dating student David Niehaus, finding a semblance of domestic life. When she started using again, he ended it. “On stage, I make love to 25,000 people, and then I go home alone,” she famously told the press.

Joplin sought clinical treatment for alcoholism and began recording her final album, Pearl, with new ensemble Full Tilt Boogie Band. Amid the cycle of recovery and relapse, she appeared optimistic. She and the band were hitting their stride, she’d even begun to discuss marriage with a new boyfriend. Joplin talked about scaling back to live a quieter life, but would just as quickly change her mind. “I know no guy ever made me feel as good as an audience,” was more than just a media-savvy sound bite. She was also aware of the double standard to which women were held. Wild men could expect a wife to stand by them, women, she felt, were not afforded the same liberty.

On October 4, 1970, Joplin was found dead of a heroin overdose at the Landmark Hotel in LA, just two weeks after Jimi Hendrix had met a similar fate. She’d spent her last day in the studio listening to a track the band had laid down – poignantly titled “Buried Alive in the Blues”. Pearl was released the following year and held the number one spot for more than two months. It’s still considered one of the greatest rock albums of all time.

Despite a tragically short life, Joplin had an enormous impact on music history, paving the way for the countless female artists who came after her. She was a white woman who sang the blues, a self-described ugly duckling who dared to put herself centrestage and, above all, a stubborn testament to her guiding mantra: “You are only as much as you settle for.”

This article originally appeared in the October issue of marie claire.