The last “normal” meal Plestia Alaqad had in “normal” Gaza was hot chocolate and pizza on the evening of October 6, 2023. Hot chocolate and pizza: it’s an odd combination, she admits, but looking back, it’s one that would seem utterly, well, normal.

The morning after that dinner with her friend Yara, Alaqad woke to news that Hamas – the militant Islamic group that controls the Gaza Strip in Palestine – had attacked Israeli communities around Gaza, killing 1200 people and taking 251 hostages.

The Israeli government in retaliation launched an attack on Gaza and began bombing the Strip, aiming at Hamas targets but primarily killing civilians. (At the time of reporting, the number of Palestinian deaths has reached more than 50,000.)

Alaqad was still half asleep when her phone started buzzing with messages about the bombings. She skimmed the group chat and, not thinking much of it, went back to sleep.

Read that again: not thinking much of the flurry of texts about her city being bombed, Alaqad went back to sleep. How accustomed to bombings do you need to be to be able to fall back asleep after hearing that kind of news? The answer is, very. Her mother, hearing the bombs fall in the night, thought it was raining. She got up, brought the washing in and went back to bed.

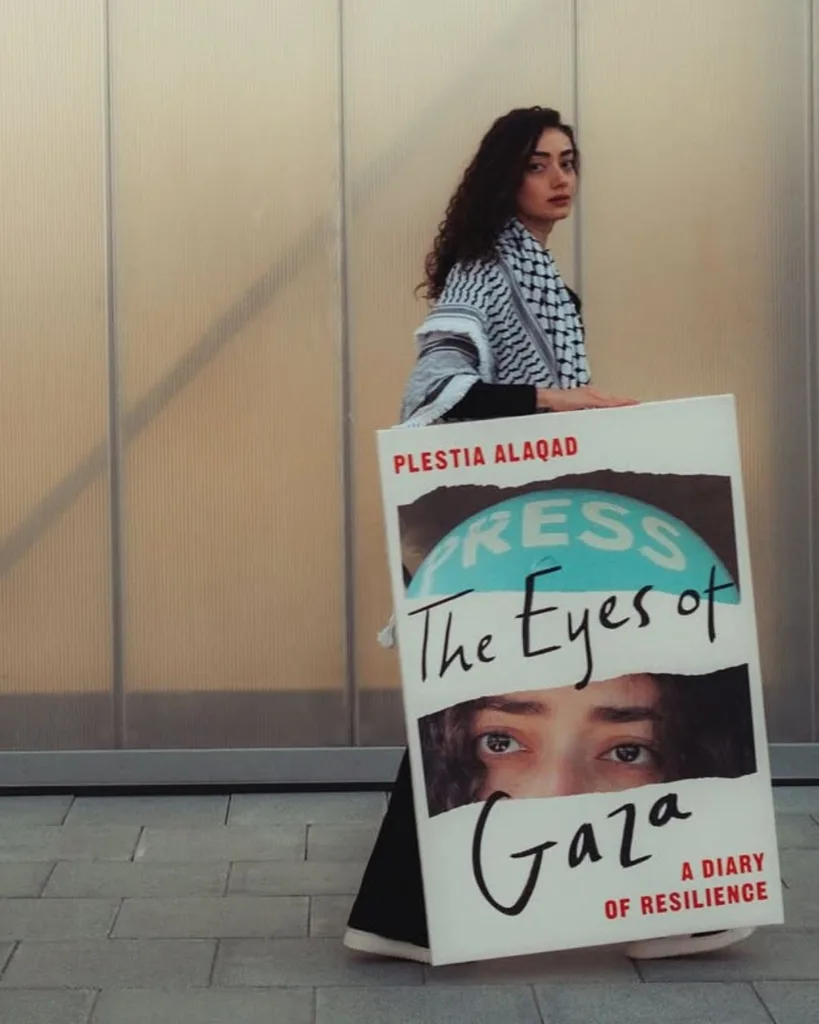

“I thought that was hilarious,” Alaqad writes in her upcoming book, The Eyes of Gaza, a series of diary entries from the first 45 days of the war.

Then she reflects: “How much trauma does it take to start thinking that bombs are like rain? And how much trauma does it take to consider that funny?”

Alaqad always wanted to be a journalist. She had studied and worked abroad and in Gaza, and when the attacks began she grabbed a press helmet and bulletproof vest and refused to be left behind by her two male colleagues, Mohamed and Hatem, who were heading off to gather footage across the region.

For a month and a half, the three of them practically lived in their car – eating whatever snacks they could get their hands on as rations dwindled and aid was halted, strategically sipping water in case that was it for the next few days, and spending hours on end searching for fuel and bread. They scurried between makeshift camps, bombed-out homes, hospital shelters and multiple evacuation relocations to give live interviews to international news outlets.

Alaqad was also posting to her Instagram in a desperate attempt to bring the world’s attention to Gaza. It worked. A video of her spontaneous reaction to a bomb going off nearby went viral. In it, she’s filming inside a house when suddenly there’s the sound of an explosion and her hair blows around her face.

She’s stunned, but doesn’t flinch. She calmly tells the camera she’s going to go and check on her parents.

There often wasn’t electricity to charge her devices and she rarely had internet – often just enough to slowly upload one video a day, a miniscule amount of the footage she actually captured – so she didn’t notice as her follower count crept up into the multiple millions and she became known to the outside world as The Eyes of Gaza. Alaqad has seen more atrocities than anyone should in a lifetime, let alone someone so young.

In her book, Alaqad describes herself as “four Israeli Aggressions old”. (She was 21 when this one began. She’s now 23.) That’s a lot of trauma, and so The Eyes of Gaza is written with a lot of dark humour.

She writes about being worried about having to evacuate halfway through a shower (“the quickest showers of my life have been those that I’ve taken during Aggressions”); about how she never learnt the name of one of her hosts, but assumes it was “probably Mohamad” (“nearly everyone in Gaza is called Mohamed”); and how relieved she was while sheltering with neighbours during a raid that they wouldn’t need to clean up after lunch (“we might get killed any minute, so who cares about the dishes?”). When asked about her use of humour, Alaqad starts to speak and then catches her reflection. “Wait,” she says. “I don’t like my hair.”

Her comedic timing is startling. Alaqad has seen orphans in hospitals, dead babies wrapped in blankets on the street; her building was bombed and she was separated from her family. On day eight, she couldn’t believe she was still alive.

She’s heartbroken and traumatised, and yet here she is on a Zoom call making me laugh, and laughing too. Of course, it’s not funny. Alaqad and I are speaking barely a week after the ceasefire that seemed to promise an end to the fighting was broken. “I did use humour [in the book] on purpose. I can’t generalise because different people cope differently, but for me it’s a coping mechanism and I do think it’s the spirit of Palestinians,” she says.

“Realistically speaking, no-one is crying 24/7. Yes, we’re crying on the inside 24/7, but we try to cope using a sense of humour. It’s not funny, but this is all we’ve got, so we’re going to try to cope and push through. That’s something humanising about Palestinians. “Usually when you learn about Palestinians, it’s through TV or the news and you see them in a specific way – for example grieving in a certain way,” she continues. “You see them as a news story not as humans, how they are behind the scenes, their sense of humour. So that’s why I made sure to show that.”

Reading The Eyes of Gaza with Alaqad’s Instagram open at the same time is a powerfully visceral experience. You can read a few days’ worth of entries, and scroll back to what she posted on those dates. It makes those posts – after which her followers would likely have been served a post by a tradwife or fit-fluencer, as is the nature of Instagram – all the more potent, and her diary entries all the more real.

“The reason I decided to make a book out of my diary is because it’s a way of documenting history,” says Alaqad. “I always feel helpless – no matter what I’m doing it’s not enough, I need to do more. So this is my way of helping, by writing history [and] hoping future generations will read it and get something out of it, because a lot of the footage that is online is getting censored.” She points out there’s also less news coming from inside Gaza because journalists are being killed.

To date, between 170 and 206 have been killed, including two on the morning Alaqad and I are due to speak. Alaqad’s career made it increasingly unsafe for her and her family to stay, and she was forced to flee Gaza with just 24 hours notice.

Her last meal was a candy bracelet she shared with Mohamed and Hatem. It was all they had – and a far cry from hot chocolate and pizza in a restaurant with water views. How much can change in 45 days.

The last page of Alaqad’s journal jumps to January 19, 2025: the day the ceasefire was announced.

It had been agreed that over three phases, Hamas and Israel would exchange hostages for prisoners, aid trucks would be allowed back into Gaza, and the Israel Defense Forces would retreat from the area. For eight weeks, Palestinians had hope; they returned to the shells of their homes and started to think about rebuilding their lives.

But on March 18, Israel’s bombing resumed. Alaqad’s morning routine once again involved checking her phone to see which of her loved ones made it through the night. In her book, Alaqad refers to ceasefires as “the space between tragedies”. “This ceasefire is not an end, it’s a pause,” she predicted. “Wars do not end when the bombs stop falling. They linger in the minds of those who survive and in the void left by those who do not.”

“The ceasefire obviously gave [the people in Gaza] hope because they are desperate for hope, they are desperate for the day the bombings stop – but that doesn’t make it any easier,” she says now. “When the bombs stopped, many people went back to their homes and discovered that [they had been] bombed. There are people still under the rubble because families and parents didn’t get the chance to bury them [before having to flee], so they’re trying to search for them.

“People started moving around during the ceasefire, and everyone was surprised by the scale of demolition. But it also gave them hope, like, ‘At least we will sleep knowing that we won’t wake up to the news of a loved one being killed,’” she adds. “But now we’re back in that loop. It sometimes feels like the only guarantee in Gaza is eventually death, because no matter how much you try to escape that loop, you keep getting stuck in it, so people are tired. The situation leaves you speechless.”

For her reporting on Gaza, Alaqad was named one of the BBC’s 100 Women in 2024, and won the One Young World Journalist of the Year Award, the Lyra McKee Award for Bravery and a Human Rights Defender Award. Her work has appeared in Al Jazeera, The New York Times and The Washington Post. She also delivered her first TEDx Talk last year. All of this, even though she didn’t set out to be a war correspondent.

She wanted to be a journalist so she could write about the beauty of her homeland, Gaza, a place much of the world knows as an “open-air prison”. The Eyes of Gaza may not be the type of reporting Alaqad wanted to do, but in it she’s achieved her goal of capturing the beauty of Gaza: the resilience of its people, their love and community. Even though her body is elsewhere, her heart is still in Gaza – the most beautiful place on earth – waiting for her to come home.

The Eyes of Gaza, by Plestia Alaqad (Macmillan), is out now.