For Amy Halvorsen, the summer of 2021-22 replays in dark, disjointed flashes. Sixteen-hour shifts, sweaty PPE “like being wrapped in hot plastic”, and a potent mix of fear and fatigue hanging in the air. “It’s a surreal fog,” says the 32-year-old, who worked as a nurse in the neurosurgery and trauma wards at Sydney’s Westmead Hospital.

As Omicron cases surged around the country, hospitals – despite contrary declarations from politicians – struggled to cope. In New South Wales, ambulances were banked up outside emergency departments for up to five hours, triage tents were erected and patients were treated in corridors and hallways, with resuscitation rooms crammed full.

Then, in the first week of January, more than 3800 healthcare workers were furloughed due to Covid exposure or infection, leaving those still standing feeling more vulnerable than ever. “That was scary and confusing,” remembers Halvorsen. “We had no management [handling the crisis] – they were all on holidays. In my ward we were two nurses down on every shift; in a team of six or seven, that’s a third of our staff gone. To put that into perspective, that’s [a loss of] one set of hands for CPR, and one person running to get the drugs to resuscitate someone.”

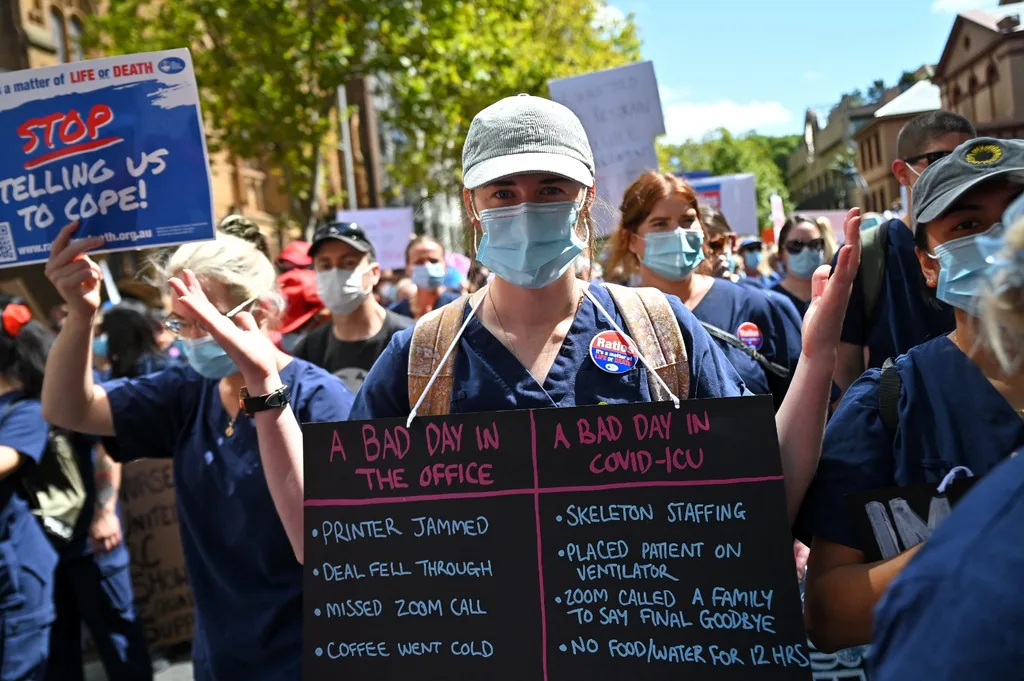

Halvorsen, who had pursued nursing after watching her mum fight breast cancer when she was a teenager, felt crippled by the pressure and “dangerous conditions”. “As a nurse, what happens when I find out nobody’s available to replace me at the end of my shift, but I’m treating a patient on a ventilator? What do I do? Of course I stay.” Her purpose and passion, too, were becoming buried in the chaos. “I felt like I wasn’t doing what I signed up to do, that I wasn’t helping anyone anymore,” she explains. “Patients were getting frustrated and we weren’t able to give them the care they needed.”

In mid-January, with no end in sight, Halvorsen hung up her scrubs for the last time. “I saw how things were unrolling and thought this isn’t worth it,” she says. “I knew that if something catastrophic suddenly popped up in my life, I wouldn’t have been able to cope.

I actually wouldn’t be here today. I decided I’ll do less damage if I get out of here. So I quit.” Halvorsen is one of hundreds of thousands of health workers who have fought on the frontline of Australia’s pandemic response. Now, two years into the largest public health emergency in our lifetime, studies reveal the psychological toll it’s taking on the workforce. These issues will disproportionately impact women, given that they hold 78 per cent of healthcare and social assistance jobs nationwide.

Globally, more than one in five healthcare workers experienced anxiety, depression or PTSD in 2020, and soon-to-be published research by Australia’s Black Dog Institute found that more than 90 per cent of healthcare workers are suffering severe burnout. The organisation says demand for its healthcare worker support service (both online and in-clinic) has spiked dramatically: up from about 5000 users prepandemic to 50,000 users today.

Most alarmingly, in a confronting healthcare workers reported thoughts of self-harm or suicide during the pandemic. “We’re seeing more and more health workers report really severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress,” confirms Dr Peter Baldwin, clinical psychologist and researcher at Black Dog Institute. “Suicide ideation and suicide itself are becoming concerningly common.”

He shares that, just hours before speaking to marie claire, he was informed of “another nurse who’s died by suicide”. While the individual remains anonymous, Baldwin wants to spotlight the tragic ripple effect. “Here, we have another nursing unit keeping the hospital running and treating people with Covid, all the while trying to deal with the fact their colleague who was here yesterday is no longer here today. That’s something that should stop everyone in their tracks.”

Indeed, the coronavirus pandemic has affected every sector of society, but as the already under-resourced hospital system buckles under strain with no clear end date, a question must be raised: who is caring for caregivers?

“There’s a huge disparity between then and now,” comments Kathryn, an operational nurse manager in the emergency department of a large NSW hospital. “There was so much gratitude for healthcare workers at the start of the pandemic, and although that was a stressful, uncertain time, it was actually really quiet in [Australian] hospitals.

Now there’s less empathy, even though the situation is much worse.” The 38-year-old says that the Delta wave in 2021 nearly pushed her to breaking point. Treating gravely ill patients was not only distressing but isolating – her whole world became Covid – and staff morale was low.

“There were nurses who were so overwhelmed they were crying in wards,” she remembers. “I’ve never really had [mental health] issues. As a healthcare worker you’re used to being punched, kicked and spat on – you can take a lot. But after that wave I experienced big burnout. At home I cried a lot and had constant fatigue. The whole reason you become a nurse is to help and care for people, but on some days you do lose your love for the job. It’s too much. You think, ‘Why am I doing this?’” It’s a sentiment shared by a number of paramedics in Victoria, who spoke to marie claire about their gruelling shifts – 17 hours wearing respirator masks, rarely able to remove them to eat or drink – and extreme staff shortages.

Each paramedic interviewed for this story also speaks of their love for the profession, and emphasises that they were grateful to have a job while others couldn’t work in lockdown. This strong sense of service and stoicism are common characteristics of healthcare workers, says Professor Marie Bismark of the Centre for Health Policy at the University of Melbourne.

She led the recent study into self-harm and suicide ideation, while also working in psychiatry in Victorian hospitals during the state’s second wave. “I’d walk around the ward and see doctors, nurses and physios all smiling and providing patient care without complaint,” she recalls. “At the same time, I was analysing the research findings and discovering that one in 10 of them was having thoughts of harming themselves, or thoughts that life was not worth living.”

The study found that fewer than half the healthcare workers who reported self-harm or suicide ideation reached out for help. “Some healthcare workers told us they knew they needed help, but that they were so exhausted they didn’t have the energy or time [to seek it out],” Bismark explains. “A lot of hospitals offer Employ Assistance Programs, but we found that very few healthcare workers used them. I think there’s a sense that unless you’re talking to someone who works in healthcare, they may not understand … There’s also still some internalised stigma … and doctors and nurses feel they should be strong and resilient.”

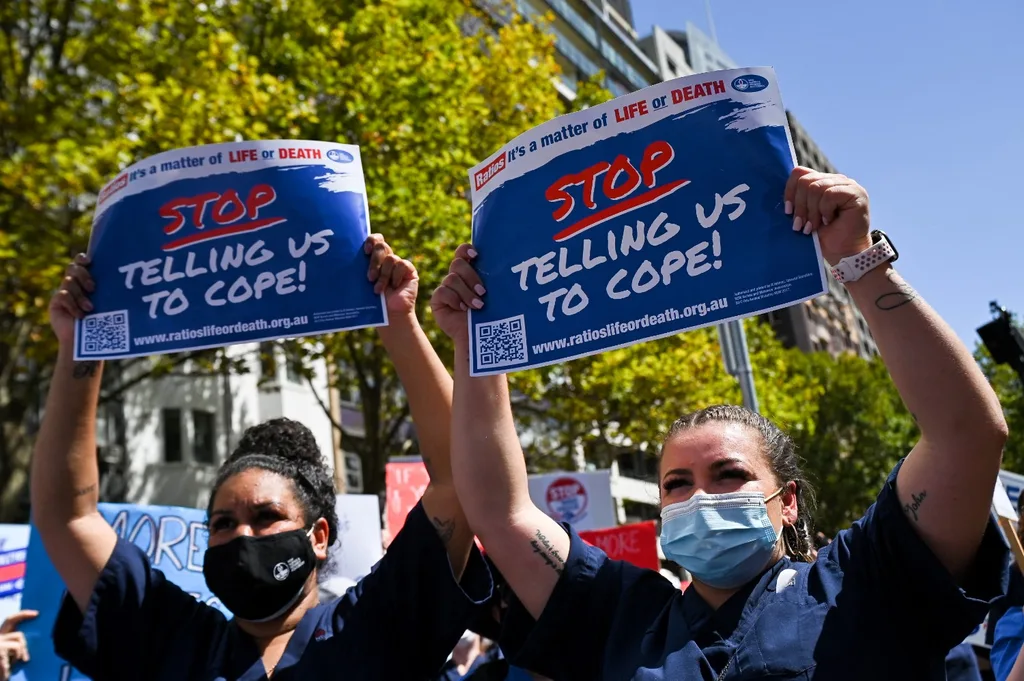

Then there are the staff shortages – an ongoing issue in Australian hospitals, but one that the pandemic has held a magnifying glass to. It’s why thousands of NSW nurses walked off the job on February 15 this year – the first time in a decade – to demand fair pay and staff-to-patient ratios (these are already legislated in Victoria and Queensland). Action is critical given the future remains clouded in haze. The emergence of new variants, a bad influenza season, the knock-on effects of delayed surgeries and a possible surge in long-Covid cases will all stretch and strain the hospital system. Experts predict that a return to normality could take between two and 10 years, making “living with Covid” a very different proposition for healthcare workers.

“Doctors and nurses have said that in any given crisis there’s usually an end date, but with the pandemic they don’t have that light at the end of the tunnel,” says Baldwin. “In a really high-stress environment, it’s hard to get up and go if there’s no light. These workers have guts of solid steel, so if they’re finding it difficult, that’s saying something … We’ve got to support them.”

If we don’t, this shadow pandemic – a dark undercurrent rippling through hospitals – will leave staff traumatised and depleted. Australia could see a mass exodus reminiscent of the US, where one in five healthcare workers has quit since February 2020.

Halvorsen herself feels a wave of relief tinged with sadness after walking away from the job she once loved, but continues to advocate for her colleagues. “I’d like to put a message out to healthcare workers: to find your voice and power in a way that feels safe for you. Tell people you’re not coping, and together let’s change it,” she says. “If you’re struggling with your mental health, you need to put yourself first. You’re not going to help anyone if you’re not here anymore.”

If this article has raised any concerns, please call Lifeline on 13 11 14, or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.

This article originally appeared in the April issue of maire claire.