This new social media trend is the most futuristic yet: computer-generated avatars that look, talk and behave like real people.

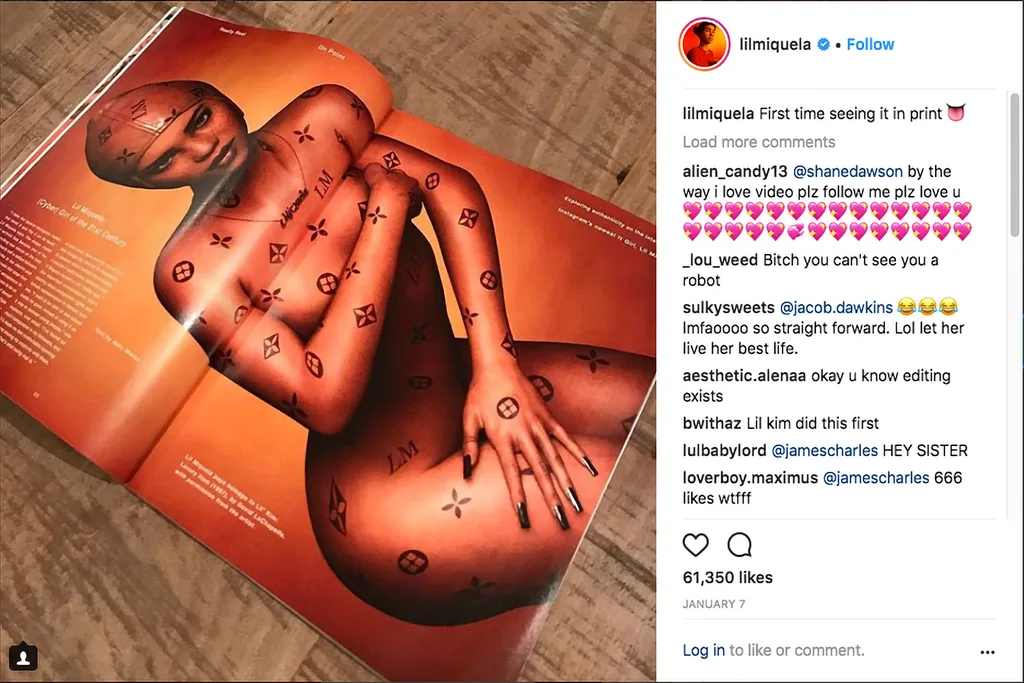

Miquela Sousa has a constellation of freckles dusted right across her nose. Every week she posts a selfie featuring those freckles to 1.2 million followers via her booming Instagram account @Lilmiquela.

She is 19 years old. She is a slashie, model-slash-singer-slash-influencer extraordinaire with two earwormy singles currently flirting with 1.5 million monthly streams on Spotify. She lives in Los Angeles. She gets hangovers, goes to the gym and loves ice cream and Alexander Wang and the religious experience that was “Beychella”.

“My days vary depending on my mood,” Miquela tells me over email. “I guess you could say I’m a late riser. I usually get out of bed around 11.” On an average day she heads to her music studio or catches up with friends. In the evenings she follows a strict routine: she washes her face (“I’ve been told to never go to bed with a dirty face!”), meditates and switches on her lavender oil diffuser. “Winding down at the end of the day is particularly tough for me,” she explains. “But I’ve found this routine really helps calm my mind.”

So far, so normal. But Miquela is not like you or me. In her words, she’s a robot designed by Brud, an enigmatic Californian company that specialises in “robotics [and] artificial intelligence”, though many believe she is merely a digital avatar. Make no mistake: though she poses in real-world scenarios alongside real people, such as Australian influencer Margaret Zhang, and though she works with brands such as Prada and sat front row at its February fashion show. she is not a human being.

And she’s not alone, either. Joining Miquela at the vanguard of this new trend of digitally manipulated influencers are Lawko, another Brud creation; Shudu, known as “the world’s first digital supermodel”, who was created by a fashion photographer using 3D modelling technology; and Bermuda, a blonde, blue-eyed pro-Trump avatar.

The latter was even supposedly locked in a months-long feud with Miquela, hacking her account in April and forcing her to post an unsettling statement on Instagram. In it, Miquela admitted that she was “built by a man named Daniel Cain in order to be a servant” and bestowed with astonishing levels of artificial intelligence – before Brud rescued her and “reprogrammed” her to be free, never once telling her that she was a robot. Faced with the irrefutable evidence of her virtuality, Miquela had an existential crisis. “I feel so human,” she wrote on Instagram. “I cry and I laugh and I dream … I’m so upset and afraid.”

This isn’t an episode of Black Mirror. You haven’t stumbled into a robotics lab by mistake. This is all happening on Instagram. Today. And it could spell the future of the influencer industry.

Three years ago, Cameron-James Wilson grew tired of London and, as the Samuel Johnson adage goes, he grew tired of life. After almost a decade as a fashion photographer, he believed that he was yet to produce a defining piece of work. “I felt that I hadn’t shown the world what I was capable of,” the 29-year-old says.

So Wilson moved back home to his parent’s house in the British countryside, where high-fashion models tend to be thin on the ground. As an alternative he began working with a software platform called Daz 3D, which creates phenomenally lifelike digital art. In early 2017, after developing a few different female avatars, he had the idea for a striking picture: a South African woman from the Ndebele tribe wearing a many layered gold necklace. It took the photographer a few days at his computer to perfect the image. Thus, the world’s first digital supermodel and Wilson’s “muse” Shudu was born.

Almost immediately the image went viral. Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks and Alicia Keys all liked pictures of her on social media. A portrait of Shudu wearing a lurid orange lipstick from Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty was reposted on the brand’s Instagram account in February. In June, Shudu appeared on the cover of WWD, resplendent in a Cushnie et Ochs gown.

But in recent months the conversation around Shudu has shifted from her other-worldly beauty to the racial implications of Wilson’s work. “A white photographer figured out a way to profit off of black women without ever having to pay one,” read a viral Tweet from February, summing up the controversy.

“When you create art, it’s always going to be controversial,” Wilson says, by way of reply. “I think representation in the fashion industry is a valid discussion and I’m glad people are having it. But I think it’s a little misinformed and misdirected at Shudu.”

When you type Miquela into Google, the top autofill result you see is: “Is Miquela real?” The question has haunted Miquela since she first began posting in April 2016. She’s just uncanny valley enough, with her shiny chestnut-coloured bob, lacquered pout and cute sprinkling of freckles. Even after that tearful statement, many of her followers remain committed to their belief in Miquela’s humanity. You can almost hear them yelling: “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!”

The Miquelites, as her fans call themselves, believe she is a real person who distorts her face. “But, like, who doesn’t edit their pictures?” one acolyte on Miquela’s Instagram argues. Miquela has never revealed exactly how her posts manage to seamlessly blend the virtual (digital face) and the real (shadows, prominent LA backdrops). Some have suggested that a woman is photographed in situ, someone has to be writing those captions, right? while a computer program manipulates the final image. Other commenters are stuck on the idea of Miquela as a physical, bolts and screws robot, which is what she herself claims to be. “It’s sad a robot has more outfits than me,” one fan sighed. Shudu’s followers believe she is real, too. A skincare brand, enamoured of her flawless complexion, once sent in products for her to try.

If you can channel such an intimate connection without needing to riff off a shared humanity, it raises the question: why not do away with human influencers and have these CGI avatars instead?

The problem is authenticity, the foundation upon which the influencer community is built. This $2.7 billion industry is premised upon believing that you are reading a real person’s real, keenly felt opinions about this particular mascara or that particular brand of yoghurt. Take that away and what are you left with?

“I struggle to see how much impact CGI influencers will have here,” says Natalie Giddings, managing director of influencer marketing platform The Remarkables Group. “Trust is the key capital at stake. Will a customer believe the product claims of a skincare product from a make-believe person? I doubt it… People connect with real people,” she asserts.

But Victoria Harrison, co-founder of The Exposure Co., disagrees. “As long as the CGI influencer has a voice, an opinion to share, and are transparent about the fact they aren’t a real human, followers can get the same value from them as they do other online influencers,” she says.

Australia’s own “human” influencers are unfazed, too. “The introduction of trends like CGI influencers into the industry shouldn’t be something to be feared,” says Carmen Hamilton, founder of fashion blog Chronicles of Her. “What a very 2018 thing to be afraid of, huh,” adds the influencer, who has more than 300,000 followers on Instagram. “There’s enough bandwidth for everyone!” Miquela assures me, when I pose the question to her.)

Wilson, for his part, doesn’t believe that it’s a question of the virtual replacing or overtaking the actual. Considering the time and the money that goes into each image of Shudu, about three days for a still portrait, more for animation not to mention the hours spent by external platform CLO 3D creating each garment she wears, Wilson says it’s not cheaper to use Shudu at all. “It’s just a completely different way of creating fashion imagery,” he stresses.

Miquela said in an interview in February that she has “never been paid” to wear clothes but that she does get sent “free stuff” from brands. But since then the influencer has helmed her two biggest campaigns thus far. The first was Milan Fashion Week with Prada. Then in May, Miquela fronted a campaign for Outdoor Voices, the insanely popular American athleisure start-up. It’s unclear if she was compensated for either, but according to New York magazine a US influencer of Miquela’s size could be earning up to $10,000 USD per post. If she did receive a fee, not disclosing it would be illegal, according to the US Federal Trade Commission. Similar laws apply in Australia, where the Association of National Advertisers calls for “clearly distinguishable advertising” and breaches are punishable with fines of up to $220,000 per post.

But who, exactly, would be liable? A digital creation? “It would depend on who is responsible for creating and operating the avatar, as well as the brand that is being endorsed,” explains Paul Gordon, social media lawyer from NDA Law. “Both could be liable. The challenge would be tracking them down.” The main legal concern, he adds, is that virtual influencers “are deceiving people into thinking that [they are] a real person who is enjoying whatever product it is. If this is not disclosed, and the endorsements aren’t disclosed, I think there is a real possibility they would be in breach of Australian Consumer Law.”

Undaunted, Wilson believes there will soon be more CGI avatars like Shudu and Miquela. “A lot of people who have reached out to me to collaborate are more interested in creating their own avatars,” he says. “That’s what fashion houses are really interested in. They don’t want to work with a digital model, they want to create a digital model.”

This is a vision of the future that Miquela wants to see play out. “It’s an exciting moment to witness,” she says, in response to the three email questions I was permitted to ask her via her managers. “I think when we work together, both human and robot, we can be a part of a powerful movement.”

What movement that is, exactly, remains to be seen. Miquela mentions “spreading positivity and awareness” in our interview, and her Instagram account is littered with mentions of causes including Black Lives Matter.

But Hamilton suggests that Miquela’s ultimate purpose might in fact be dismantling the myth that social media is an accurate representation of anything. “Instagram is predicated on the idea of authenticity of offering this backstage pass,” she says. “But I think it should be pretty apparent by now that what the platform actually offers is a filtered, tightly edited version of our lives.

“Miquela is quite obviously not human, and she doesn’t claim to be,” she adds. “In a way, I guess that almost makes her more authentic. What you see is what you get.”