Pop culture assassins are a guaranteed hit, and never has our collective fascination for recompense and revenge been so heightened, as now.

Our screens are forever being splattered with morally questionable, yet no less likeable, triggermen (and of course, women), cashing out their scruples to satisfy the fancies of the highest bidder; Our feeds filled with feats of righteous reckoning, carried out by avatars of espionage.

Of course, most recently, we’ve seen the enduring antihero trope assail the fourth wall and spill out onto the streets of New York. Where an act of perceived retribution was delivered so brazenly, it felt more like the stuff of scripted mercenary make-believe, than of the realm of reality in which it occurred.

The act in question was of course the killing of the UnitedHealthcare CEO, whose methodical murder was carried out in broad daylight by the alleged assailant, 26-year-old Ivy League graduate, Luigi Mangione.

As surveillance footage of the slaying made its way across the internet, sentiment rapidly shifted to expressions of camaraderie over condemnation. Memes that ran the gamut from praise to straight-up thirst began circulating in response to the titillating tale of the vengeful vigilante figure, and a nation’s simmering discontent with corporate greed found its non-fiction figurehead in the process.

“It felt like something literally out of a movie,” said producer Adrian Askarieh in response to the events in an interview with Vanity Fair.

Askarieh, whose filmic repertoire includes the screen adaptation of popular assassin videogame Hitman: Agent 47 , posited that the public’s almost desensitised response was likely due to a sense of justice served by proxy.

“One of the reasons the idea of an assassin has been so fascinating, going back to movies like Le Samouraï with Alain Delon, is that there is a catharsis that comes with the assassins doing what we can’t see ourselves doing,” he said.

“I think it’s more of a vicarious experience. A lot of human beings feel helpless and want to vicariously live through those characters.”

So why are we so obsessed with the idea of killers with a conscience?

All Hail The Pop Culture Assassin?

There’s definitely something to be said for the appeal of a ruthless pop culture assassin character carrying out a Robin-Hood-esque style of retribution. Whose ability to enact a perceived level of justice – however flawed and whatever the justification – could be viewed as innately human, or perhaps even revenge fantasy manifest.

Few people can say they’ve ever (knowingly) encountered a hitman, yet they’re so ubiquitous as part of today’s action genre, that it’s almost as if the vocation of ‘espionage professional’ or ‘gun-for-hire’ could find itself a neat little spot on the career counsellor’s list of most viable post-grad pursuits.

This enduring quality ascribed to our favourite on-screen mercenary murderers is largely thanks to our ability to separate the antihero from the true villain – or rather – assign a level of moral superiority to a gun-for-hire or spy with scruples, over say – a far less likeable serial killer.

In Netflix’s new trigger-happy action thriller series Black Doves, professional spy Helen Webb (played by Keira Knightley) is thrust into a murky world of subterfuge and geopolitical games after her lover is murdered.

Enlisted to protect her on her quest to enact revenge is Sam (played by Ben Whishaw), a friend, ex-colleague and retired assassin, whose own past comes back to haunt him and confront his own binding sense of steadfast, yet conflicting, principles.

In one episode, a flashback scene between Helen and Sam, where Helen draws a line between her work (then-junior espionage with a touch of assassin lite) and his (full-time contract killer), she says “I could never kill people for a living.”

Sam responds with an emphatic: “It’s not what you think,” before Helen retorts, “Well, it’s murdering people, isn’t it? So it is what I think it is.”

After a brief interlude, Sam reveals his character’s underscore as very much linked to a set of rules, or as he later calls it, a code: “I’ve never pulled a trigger that didn’t make the world a better place.”

For his part, Sam doesn’t kill kids (which proves to be a slight hiccup in the plans), likewise, any adult he does kill, is seemingly deserving of his silencer’s wrath.

These “codes” we find out further on, are inherited, and subsequently passed on to fellow assassins Williams and Eleanor as a rallying raison d’être to elicit an alliance.

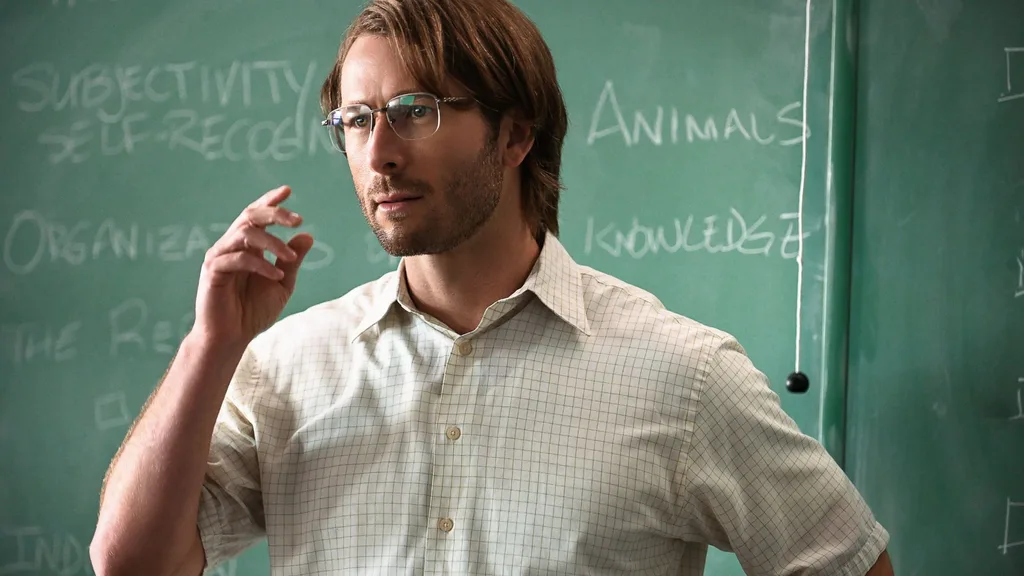

In the same year, Richard Linklater’s romcom turned hitman hustler film, Hit Man, starring Glen Powell, was another addition to the booming pop culture assassin genre. Though Powell’s Hit Man is less about a real hitman, and more a love letter to the allure of the fictionalised triggerman, in all its multilayered glory.

Playing into the more classic of the hitmen tropes, Eddie Redmayne’s The Day of the Jackal appeals to those who prefer their cutthroats to be masters of skilful subterfuge and swift redemption – often exerting power where most would feel powerless. Are we noticing a pattern here?

Then there’s the complexities explored in Killing Eve’s perfectly-imperfect Villanelle, or Colin Farrell’s positively loveable character in In Bruges, and Kill Bill’s katana-wielding Beatrix “The Bride” Kiddo hellbent on vengeance.

And who could forget John Wick, a protagonist with undeniably homicidal tendencies who comes out of retirement to seek retribution for the murder of his beloved dog (there’s slightly more to it, but that’s basically the gist) leading to a four-part franchise and hundreds of casualties.

In a world of constantly shifting measures of morality, one person’s tyrant or terrorist is another’s rebel with a cause. We’ve been conditioned by such on-screen depictions of spies, assassins and hitmen over the years to root for their fictional counterparts without question.

It’s no surprise then, that to so many people, this is indeed what a hero looks like.